Watch this animated clip for a quick overview.

On 15 April 2019, the European Council approved the Directive on Copyright and Related Rights in the Digital Single Market. This Directive intends to make EU copyright rules fit for the digital age. Unlike regulations, the Directive is not directly applicable and will require the transposition into the national legal systems of each member state.

The digital age has transformed the way in which researchers carry out their work, how we conceive business and share knowledge and information. Current copyright rules are not adapted to the growing digital landscape – a fact which made it necessary to bring these rules up to speed and offer an appropriate regulatory framework that encourages creative work and innovation while striking the balance with freedom of expression and the need to promote research, education, access to information and cultural heritage.

In this fact sheet we provide you with an overview of the most important changes and legal implications, and take a look at the next steps.

Article: Copyright and Cultural Heritage

This article written by Dr Paul Klimpel is partially based on a keynote speech given by Dr Paul Klimpel (iRights.Law) at a workshop with representatives of different cultural heritage projects.

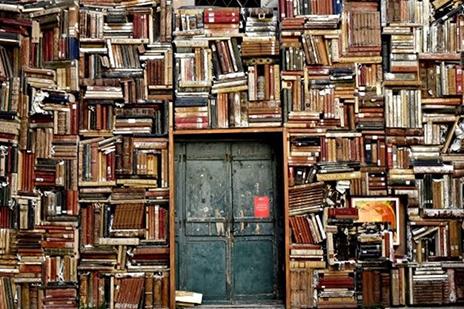

Europe’s galleries, libraries, archives and museums have vast collections representing European cultural diversity, shared history and values. In addition, Europe has many historical buildings, archaeological sites and monuments as well as intangible cultural heritage, such as cultural festivals or craft making techniques, which are known around the world. Digital technologies and the internet provide citizens with unprecedented opportunities to access cultural material, while the institutions can reach out to broader audiences, engage new users and develop creative and accessible content for leisure and education.

On the other hand, creators such as authors, musicians, poets, painters etc. need to control how their works are used, by whom, and on what terms. Adopted in 1886, the Berne Convention deals with the protection of works and the rights of their authors. But especially when it comes to the use or reproduction of older art works or pieces of cultural heritage, very specific copyright issues may arise. Oftentimes, it is very difficult or even impossible to clarify the copyright status with certainty.

Within the field of application of the Revised Berne Convention, copyright legislation follows clear principles almost around the world. Initial copyright protection of any given work is usually connected to the author as a person and arises automatically, without any formalities involved. The author can then grant various rights to use the work or, in some jurisdictions, sell the rights for good. Only those who somehow obtain these rights are allowed to make use of a work, unless an accepted limitation or exception applies.

Limitations and exceptions aside, legal use of a copyright-protected work rests on a gapless sequence of transfers or grants of suitable rights from the creator to the user. This also applies to cultural heritage, and thus to works where the exploitation cycle has usually ended long ago. Due to extended protection periods, most works of the twentieth century are still under copyright protection. Nevertheless, it is often unclear who holds which rights in older works today – in particular regarding digital uses which weren't even known at the time the work was created.

A lack of contractual accuracy about what was transferred (especially in old contracts), inexact wordings in general, the absence of rules to rectify flawed transactions – like in bona fide acquisition or usucaption – plus the absence of formal protection requirements combined with very long protection terms are the most important reasons for considerable uncertainties regarding the copyright status of older works.

In most cases it is not entirely possible anymore to decide all uncertainties and clear the legal status unambiguously. The clearing process gets even more difficult the more time has passed since the first publication or use, the longer the work has been out of use and the more creators have been involved.

These uncertainties prevent many possible and desirable legal uses of older works. They do not, however, necessarily leave older works unused altogether. The legal uncertainties are often handled rather pragmatically. The most frequent method to use a work in spite of legal uncertainties is to fictitiously ascribe the rights involved or to accept arrogation of copyright by others. The adscription of rights is a consensus of the parties involved about who should be accepted as the right holder while the arrogation of rights is a false claim of copyright. Regarding valid transfers or grants of rights, both might be entirely without effect, and yet this procedure is very common in practice.

The same can be observed for so-called orphan works, the legal owners of which are entirely unknown. Regulations based on the Directive 2012/28/EU (Directive on certain permitted uses of orphan works) have only very little practical effect, since the diligent search requirements are very high and there is a continued risk of a copyright owner appearing at a later stage. Heritage institutions often avoid to spent money on diligent search and digitalisation, because there is no certainty that they can use their collections later.

In order to handle the uncertainty of the copyright status of older works, it is unavoidable to replace right clearance with risk management. Dealing with copyright and licences is always associated with risk management, since there is no bona fide acquisition of copyright and so there is always a risk of copyright fraud and the invalid purchase of a licence.

Reflecting this, heritage institutions should put much effort into the rights clearance while also accepting a certain degree of risk. They always should keep in mind that an allegation of copyright infringement needs to be proven as well. If heritage institutions have a good documentation of their diligent search and their assumption of the copyright status is based on evidence, it is not likely that an infringement can be proven.

Also, such institutions should be aware of copyright fraud. The legal uncertainties in older works are exploited by companies, organisations and individuals in order to claim royalties or licence fees, even though they positively know they do not actually hold any rights in the work. Still, this approach is sometimes successful and seems to evolve into a business model of its own. As the addressees of such claims can never be entirely sure whether the alleged rights do exist or not, many of them are willing to pay just to avoid the risk of unpredictable legal proceedings. This particularly applies to heritage organisations that strongly depend on a trustful relationship with rights holders and must avoid any impression that they might flout copyright.

In order to support these organisations in increasing collaboration and using synergies with digital technologies, the European Commission has established a European cultural platform providing a publishing framework and public access to a wide array of digital content from Europe’s libraries, archives and museums. This platform, Europeana, enables and supports cultural heritage institutions in sharing their content through common standards and interoperability solutions, and in developing a network of aggregators, cultural institutions and digital cultural heritage professionals from across the EU. Moreover, the Expert Group on Digital Cultural Heritage and Europeana (DCHE) provides a space for fruitful collaboration between the European Commission and its member states as well as among the member states themselves.

For further information on the topic, please take a look at the European Commission report “Cultural Heritage: Digitisation, Online Accessibility and Digital Preservation” which reviews and assesses the overall actions and progress achieved in the European Union in implementing the Recommendation (2011/711/EU) which is one of the main EU policy instruments on digitisation, online access and digital preservation of cultural heritage material.